The Feast of St. Bernardino of Siena: May 20th

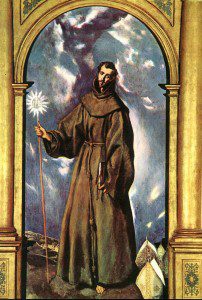

St. Bernardino of Siena

St. Bernardino of Siena

The Franciscan Bernardino of Siena, OFM, (sometimes Bernardine) was an Italian priest, missionary, and is a Catholic saint. He is most noted for his preaching and evangelizing the people of Italy during the 15th century, sometimes being called “the Apostle of Italy” for his efforts to revive the country’s Catholic faith. His great oratorical skills and persuasiveness are the reason he is the patron saint of advertisers and advertising.

St. Bernardino’s popular preaching and missions had their own banner, the letters “IHS” on the background of a blazing sun. The IHS Christogram is often interpreted as meaning Iesus Hominum Salvator (“Jesus, Savior of men” in Latin) and is associated with the Feast of the Holy Name of Jesus. When on his preaching and conversion missions to the turbulent cities of Italy, he carried with him a copy of the monogram of the Holy Name, surrounded by rays, painted on a wooden tablet. They held the symbol aloft when they blessed the sick; many great miracles were reported from these blessings – all done in the Holy Name of Jesus. At the close of his sermons, he exhibited this emblem to the faithful and asked them to prostrate themselves in adoration of the Redeemer of humanity. He recommended the faithful to have the monogram of Jesus placed over the gates of their cities and above the doors of their dwellings to remind them always of the blessings of their Lord and Savior.

Bernardino was born 8 September 1380 and passed away 20 May 1444. After his death, the Franciscans promoted an iconographical program of images of Bernardino, which was second only to that of St. Francis himself. As such, he is one of the earliest saints whose appearance was given a distinct and readily recognizable iconography. Artists of the late medieval and Renaissance periods often represented him as small and emaciated, with three mitres at his feet (representing the three bishoprics which he had rejected) and holding in his hand the IHS monogram.

Early Life

Bernardino was born into a noble family in the Sienese town of Massa Marittima. His father was governor of the district, but Bernardino was left orphaned at six and was raised by a pious aunt. At the age of 17, after a course of civil and canon law, he joined the Confraternity of Our Lady attached to the hospital of Santa Maria della Scala church. Three years later, when the plague visited Siena, he ministered to the plague-stricken, and, assisted by ten companions, took upon himself entire charge of this hospital for four months. He escaped the plague but was so exhausted that a fever confined him for several months.

At age 23, he joined the Franciscans (Order of Friars Minor). Bernardino was ordained a priest a year later and was commissioned as a preacher the following year. About 1406, St. Vincent Ferrer, a Dominican friar and missionary, while preaching at Alessandria in the Piedmont region of Italy, allegedly foretold that his mantle should descend upon one who was then listening to him, and said that he would return to France and Spain leaving to Bernardino the task of evangelizing the remaining peoples of Italy.

Bernardino as Preacher

Bernardino as Preacher

The period of Bernardino’s public engagement coincided with a time when the Catholic Church was responding actively to movements that it regarded as heretical, and which were gaining popularity in southern France and northern Italy. For more than 30 years, Bernardino preached all over Italy and played a great part in the religious revival of the early fifteenth century. Although he had a weak and hoarse voice, he is said to have been one of the greatest preachers of his time. His style was simple, familiar, and abounding in imagery. Cynthia Polecritti, in her biography of Bernardino, notes that the texts of his sermons “are acknowledged masterpieces of colloquial Italian.” He was an elegant and captivating preacher, and his use of popular imagery and creative language drew large crowds to hear his reflections. And, as Polecritti also notes, the subject matter of his sermons reveals much about the contemporary context of 15th-century Italy.

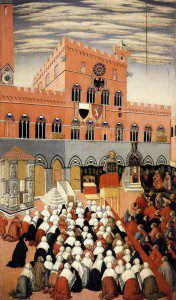

He traveled from place to place, never remaining for more than a few weeks. These journeys were all made on foot. In the towns, the crowds assembled to hear him were at times so great that it became necessary to erect a pulpit on the marketplace. Like Vincent Ferrer, he usually preached at dawn. His hearers, so as to ensure themselves standing room, would arrive beforehand, many coming from far-distant villages. The sermons often lasted three or four hours. He was invited to Ferrara in 1424, where he preached against the excess of luxury and immodest apparel. In Bologna, he spoke out against gambling, much to the dissatisfaction of the card manufacturers and sellers. Returning to Siena in April 1425, he preached there for 50 consecutive days. His success was claimed to be remarkable. “Bonfires of the Vanities” were held at his sermon sites, where people threw mirrors, high-heeled shoes, perfumes, locks of false hair, cards, dice, chessmen, and other frivolities to be burned. Bernardino enjoined his listeners to abstain from blasphemy, indecent conversation, and games of hazard, and to observe feast days.

Bernardino’s sermons were unapologetic, both while he was alive and after his death. They were of severe, moralizing temperament, and he inveighed against various classes of people he believed were particularly responsible for the moral corruption of Christendom. He spoke out against witchcraft and usury. It was this latter moralizing that has tainted some of Bernardino’s reputation. He blamed the conditions of widespread poverty on the usurious practices of the moneylenders, a guild that was almost exclusively Jewish. Finding the lending practices unbiblical, he condemned them and called for the community to isolate the lenders. His audiences often used his words to reinforce actions against Jews, and his preaching left a legacy of resentment on the part of Jews. He thus became the moral major domo of what historian Robert Ian Moore has called “the persecuting society” of late medieval Christian Europe.

Trial in Rome

Especially known for his devotion to the Holy Name of Jesus, Bernardino devised a symbol—IHS—the first three letters of the name of Jesus in Greek, in Gothic letters on a blazing sun. This was to displace the insignia of Italian city family-political factions. The devotion spread, and the symbol began to appear in churches, homes, and public buildings. Opponents thought it a dangerous innovation. Nonetheless, Bernardino used the devotion to calm strife-torn cities, reconciling feuds and factionalism by his counsel. and performing miracles.

In 1427, Bernardino was summoned to Rome to stand trial on charges of heresy himself for his promotion of this devotion to the Holy Name of Jesus. Bernardino was found innocent of heresy, and he impressed Pope Martin V sufficiently that Martin requested he preach in Rome. He thereupon preached every day for 80 days. Bernardino’s zeal was such that he would prepare up to four drafts of a sermon before starting to speak. That same year, he was offered the bishopric of Siena, but declined in order to maintain his monastic and evangelical activities. In 1431, he toured Tuscany, Lombardy, Romagna, and Ancona before returning to Siena to prevent a war against Florence. Also in 1431, he declined the bishopric of Ferrara, and in 1435 he declined the bishopric of Urbino.

John Capistran was his friend, and James of the Marches was his disciple during these years. Cardinals urged both Pope Martin V and Pope Eugene IV to condemn Bernardino, but both almost instantly acquitted him. A trial at the Council of Basel also ended with an acquittal. Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund sought Bernardino’s counsel and intercession, and Bernardino accompanied him to Rome in 1433 for his coronation.

Franciscan Vicar General

In 1438, Bernardino was required to abandon his preaching missions when he became vicar-general of the Franciscans in Italy. Bernardino founded, or reformed, at least three hundred convents of Friars. Bernardino sent missionaries to different parts of Asia, and it was largely through his efforts that many ambassadors from different schismatical nations attended the Council of Florence, in which we find the saint addressing the assembled Fathers in Greek.

Being Vicar General inevitably cut back his opportunities to preach, but he continued to speak to the public when he could. In 1442, having persuaded the pope to finally accept his resignation as vicar-general, so that he might give himself more undividedly to preaching, Bernardino again resumed his missionary work. Despite a Papal Bull issued by Pope Eugene IV in 1443, which charged Bernardino to preach the indulgence for the Crusade against the Turks, there is no record of his having done so. In 1444, notwithstanding his increasing infirmities, Bernardino, desirous that there should be no part of Italy, which had not heard his voice, set out to the Kingdom of Naples.

He died that year at L’Aquila, in the Abruzzi. According to tradition, his grave continued to leak blood until two factions of the city achieved reconciliation.

Canonization

Reports of miracles attributed to Bernardino multiplied rapidly after his death, and in 1450, Pope Nicholas V canonized Bernardino as a saint, only six years after his death. His feast day in the Roman Catholic Church is on 20 May, the day of his death.

But did you know…

Bernardino was the great systematizer of Scholastic economics after Aquinas, and the first theologian since the Franciscan Olivi to write an entire work devoted to economics. This book, titled On Contracts and Usury, dealt with the justification of private property, the ethics of trade, the determination of value and price, and the usury question.

His greatest contribution to economics was the fullest discussion and defense of the entrepreneur written at the time. He pointed out that trade, like all other occupations, could be practiced either lawfully or unlawfully; all callings provide occasions for sin. Furthermore, merchants provide many useful services: transporting commodities from surplus to scarce regions; preserving and storing goods to be available when consumers want them; and, as craftsmen and industrial entrepreneurs, transforming raw materials into finished products.

Bernardino further observed that the entrepreneur is endowed by God with a certain and special combination of gifts that enable him to carry out these useful tasks. He identified a rare combination of four entrepreneurial gifts: efficiency, responsibility, hard work, and risk-taking. Very few people are capable of all these virtues. For this reason, Bernardino argued that the entrepreneur properly earns the profits, which keep him in business and compensate him for his hardships. These are a legitimate return to the entrepreneur for his labor, expenses, and the risks that he undertakes.