The Feast of St. Bonaventure of Bagnoregio: July 15th

St. Bonaventure of Bagnoregio

St. Bonaventure of Bagnoregio

St. Bonaventure is one of the major figures in the history of the Franciscan Friars. He was major philosopher and theologian of his day – a contemporary of St. Thomas Aquinas – both of them holding the “chairs” of Regents at the University of Paris at the same time. Like Thomas, Bonaventure was also a prolific writer and thinker, his works covering the range of theology, scripture, liturgy, music, the arts, and more. Unlike Thomas, Bonaventure was called away from the academic life in 1257, when he was elected to be Minister General of the Franciscan Order. In 1273, he was elevated to Cardinal and assigned the task of reconciling the Roman Catholic (western) and Byzantine-Greek Orthodox (eastern) churches – a task almost completed at the Council of Lyon in 1274. Sadly, Bonaventure became ill during the Council and died on July 15, 1274.

His Childhood

Actually, we know very little about his childhood. He was born in 1221 (or 1217) – five years before the death of St. Francis – at Bagnoregio, a town about 90 km northwest of Rome in the vicinity of Viterbo. It is an interesting town, only accessible by a bridge/walkway, as the town is perched on the center cone of an extinct volcano. The natural “shape” of the town is circular and scholars have wondered if that is, in part, the basis for Bonaventure’s use of circular imagery in his writings.

We know the name of his parents: Giovanni di Fidanza and Maria Ritella. We also know his given name was “John.” It is not clear how his baptismal name came to be “Bonaventure.” An attempt has been made to trace the latter name to the exclamation of St. Francis, O buona ventura, when Bonaventure was brought as an infant to him to be cured of a dangerous illness. This account is highly improbable, as it seems based on a late fifteenth-century legend. In the prologue to the “Major Legend of St. Francis,” authored by Bonaventure, he himself tells us that while yet a child he was preserved from death through the intercession of St. Francis, but there is no evidence that this cure took place during the lifetime of St. Francis or that the name Bonaventure originated in any prophetical words of St. Francis.

A Friar at the University of Paris

Bonaventure joined the Franciscans in 1238 and after four years was sent to the friars in Paris to study under the tutelage of Alexander of Hales, the Franciscan master at the University of Paris. Bonaventure first studied at the Franciscan studium only, later (1243) gaining admittance to the University proper.

For the next several years, Bonaventure lived the life of a student until in 1248 he received the “licentiate” which gave him the right to teach publicly. He continued to lecture at the university with great success until 1256, when he was compelled to abandon his teaching position, owing to the then violent outburst of opposition to the Mendicant orders (Franciscans and Dominicans) on the part of the secular professors (lay and ordained) at the university. In the 1220’s, one of the “regent” chairs was occupied by a mendicant priest – now 11 of the 15 chairs were already in the hands of the Dominicans and Franciscans – and two more mendicants were about to be installed as “regent masters” – St. Thomas Aquinas and St. Bonaventure – bringing the total to 13 of 15. Once the controversy quieted down, Bonaventure returned and was installed as a Regent Master of the University.

The Heart of Bonaventure: Minister General of the Franciscans

In the years while St. Francis was alive the Franciscan Order experienced rapid growth, which only accelerated after St. Francis’ death and canonization: each friar and local fraternity trying to discern what it meant to follow Christ in the “tradition” of Francis of Assisi. They came to several differing conclusions and the opinions were not always offered “humbly.” Over simply, one group called for poverty to be the mainstay while another called for obedience. A third group was in the middle just wanting everyone to get along because fraternity and minority were the hallmarks of Franciscan life. The Order was beginning to come apart at the core.

The Minister General of the Order, John of Parma, was unable to heal the growing factions, and so in May of 1257, the Franciscan brothers elected Bonaventure as Minister General. In the following 15 years of leadership, Bonaventure continually visited the brothers, walking from Assisi, to Padua, to Madrid, to Paris, and to all the friaries of Europe. His example of humble living coupled with his words reminding the friars that following Christ was the center of Francis’ vision, enabled the rifts in the fraternity to be healed.

His humble manner of living was on display when the Pope elevated him to the role of Cardinal. The papal couriers carrying the official proclamation and “red hat” found Bonaventure at one of the friaries in northern Italy. When the couriers arrived on the scene, Bonaventure, the Minister General of the Order, was occupied washing the dishes after a meal. The courier’s formal announcement was followed by the presentation of the red hat. Bonaventure thanked him, asked him to set the hat on the table (or on a tree in another account), and said he would attend to those things as soon as he had finished washing the dishes.

The Mind of Bonaventure: A Doctor of the Church

The Mind of Bonaventure: A Doctor of the Church

There is no way to cover the thought or work of St. Bonaventure, but it seems he wrote something for almost everyone. Scholars of medieval philosophy and theology will most often discuss Bonaventure’s writings from his academic days at the University of Paris. Church historians most often look to his writings on the medieval secular-mendicant controversies in which Bonaventure defends the Franciscan way of life as authentically Christ-centered and biblically based. Of particular interest is Bonaventure’s view on the “theology of history,” the topic of Pope Benedict XVI’s doctoral dissertation.

Among the writings most often looked to by his Franciscan brothers are his spiritual works, “collations” – exhortations on how to live a Franciscan life, and his major biography of the life of St. Francis. His work Itinerarium mentis in Deum (Journey of the Soul to God) is considered a masterpiece of medieval spiritual practice. Bonaventure wrote this work while at La Verna, the place where St. Francis received the Stigmata of Christ. The work moves into the spiritual vision of holiness with Francis as its explicit inspiration and model.

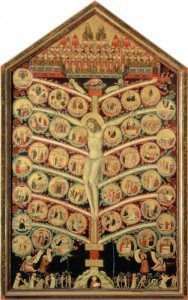

One of his spiritual works, The Tree of Life, represented a new vibrant way of writing about the life of Christ and stressing its imitation. The poetical and lyrical style of the work became a template for spreading Franciscan devotional practices throughout Europe. When the Franciscan, John of Montecorvino, was made the first Bishop of Beijing in 1292, the “cross” of the cathedral (really just a small church) was a painting of the “Tree of Life,” such was the impact of the imagery.

The Florentine artist Pacino di Bonaguida’s work “Tree of Life” hangs in Galleria dell’ Accademia of Florence. It shows Christ’s Crucifixion on a tree with twelve branches. The painting depicts the writing of St. Bonaventure’s The Tree of Life, in which he discusses the origin, the passion, and the glorification of Christ.

Other works include: The Three-fold Way – his systematic treatment of the stages of the spiritual life, Soliloquy on the Four Spiritual Exercises, On the Government of the Soul, and On the Five Feasts of the Child Jesus. It was during this middle period that he was commissioned by the friars in 1260 to write the official biography of Francis, which has come to be known as the Legenda maior, i.e., The Major Life of St. Francis. Bonaventure also composed a shorter life of Francis for liturgical use known as the Legenda minor. His biography of St. Francis helped the Order to focus on what was important about Francis as a guide in following Christ.

The breadth and scope of his writings were used, in part, in the Church’s response to the Protestant Reformation by the Council of Trent. Because of the breadth and his lifetime of work, Pope Sixtus V declared Bonaventure a Doctor of the Church in the year 1588.

Bonaventure the Churchman: A Cardinal of the Church

Bonaventure the Churchman: A Cardinal of the Church

Bonaventure was tasked by Pope Gregory X to help the Church prepare for the Council of Lyon in 1274. Bonaventure was tasked with two great projects of reconciliation: healing the schism of the east-west within Catholic Church (Byzantine or Eastern Orthodox and Roman west) and healing the growing schism between the mendicant religious orders and the Bishops/diocesan priests.

As to the latter, it is a complicated tale, but in short, it was agreed to suppress all religious orders not established before the 4th Lateran Council’s 1215 ban on new religious orders. There were two exceptions: the Dominicans and the Franciscans, both technically “established” with formal papal approval after 1215. Bonaventure’s work to heal the internal divisions among the friars was largely successful, but there were a number of friars who left the Order and formed smaller “orders” in the tradition of St. Francis. These groups were not part of the exception.

As regards to the reunification with the East, it was largely due to Bonaventure’s efforts and to those Friars whom he had sent to Constantinople, that the Eastern churches accepted the union effected July 6, 1274 and all churches were united under the leadership of the Bishop of Rome.

Bonaventure died suddenly on July 15, 1274. The exact cause of his death is unknown, but the chronicle of Peregrinus of Bologna, Bonaventure’s secretary, reports that the saint was poisoned! Suspicion has always fallen upon one of the leaders of a breakaway group of “Franciscans,” which would be suppressed by the rulings of the Council of Lyon.

He was buried on the evening following his death in the church of the Friars Minor at Lyon.

Bonaventure: A Saint of the Church

Bonaventure enjoyed especial veneration even during his lifetime because of his holy character and of the miracles attributed to him. It was Alexander of Hales who said that Bonaventure seemed to have escaped the curse of Adam’s sin. And the story of St. Thomas visiting Bonaventure’s cell while the latter was writing the life of St. Francis and finding him in an ecstasy is well known. “Let us leave a saint to work for a saint,” said the Angelic Doctor as he withdrew.

When, in 1434, Bonaventure’s remains were translated to the new church erected at Lyon in honor of St. Francis, his head was found in a perfect state of preservation, the tongue being as red as in life. This miracle not only moved the people of Lyons to choose Bonaventure as their special patron, but also gave a great impetus to the process of his canonization. Dante, writing long before, had given expression to the popular mind by placing Bonaventure among the saints in his “Paradiso.”

But it was 208 years before Bonaventure was canonized. The delay is most likely due to the recurring dissensions within the order after Bonaventure’s death. Finally on April 14, 1482, Bonaventure was canonized by Sixtus IV.

Bonaventure: Relics of the Saint

As was the tradition in medieval times, relics of the saint (or those who would become a saint) were important. At some point in time after his death, the arm and hand of Bonaventure were removed from the body and conserved at his home parish of St. Nicholas in Bagnoregio. As noted above, the remains of the saint were moved in 1434 to a new church in Lyon. In 1562, Bonaventure’s shrine was plundered by the Huguenots and the coffin containing his body was burned in the public square. It is recorded that Bonaventure’s head was preserved through the heroism of the local Franciscan superior, who hid it at the cost of his life. The local community reported that the relic disappeared during the French Revolution and every effort to discover it has been in vain.