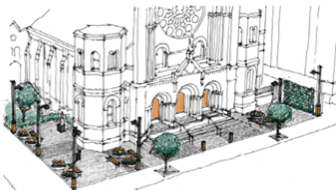

Since the arrival of the Franciscan Friars at Sacred Heart in 2005, the church has taken on several projects – most notably our plaza renovation in 2013 – which truly brought to life the sense of welcome and engagement for which the parish has become known. The project extended our “front porch” to the very edge of Florida Avenue and Twiggs Street.

In its own way, “The Wolf of Gubbio” project is a continuation of that basic renovation, with artwork that is inviting and tells a story about our community. Among the most beloved and popular stories of St. Francis is that of the Wolf of Gubbio. At the heart of the story is the willingness and capacity of the Saint to enter, with humility, into the heart of conflict in order to create a place that is holy, hospitable, and healing, and where hope can grow and take root in the lives of all people. We hope you take a moment to read the story, as well as learn a little bit about the artist who created the work.

The Story

The story of St. Francis and the Wolf of Gubbio is a story that has been told and retold throughout the ages. There are several books dedicated to the legend, a whole host of toys and hand puppets, and even a three-part play. The variety and breadth of the re-telling and reimagining speaks to the universality and appeal of the story, in which a lone wolf appeared around the town of Gubbio, “terrifying in physical size and ferocious with rabid hunger. This wolf not only destroyed other animals but even devoured men and women, keeping all the citizens in such danger and terror that when they went outside the town, they went armed and guarded as if they had to advance toward deadly battles.” This is the picture of the antagonist who will come face-to-face with St. Francis – at least as told by the citizenry of the town who, consequently, lived in fear behind their barricaded walls. The town, the people, and the wolf were in need of holiness, healing, hospitality, and hope. St. Francis, upon hearing about the incidents, responded in great compassion for the town, its citizenry, and the wolf – for all God’s creatures. He understood that every side has a story, every side has erred and been harmed, and both sides want the hope and possibility of peace. Francis went into the forest and called out to the wolf to come and meet in peace. Francis’ call was a call to holiness and began the process of healing in the moment of listening to the other, of inquiring why there was such aggressive and brazen behavior.

The story of St. Francis and the Wolf of Gubbio is a story that has been told and retold throughout the ages. There are several books dedicated to the legend, a whole host of toys and hand puppets, and even a three-part play. The variety and breadth of the re-telling and reimagining speaks to the universality and appeal of the story, in which a lone wolf appeared around the town of Gubbio, “terrifying in physical size and ferocious with rabid hunger. This wolf not only destroyed other animals but even devoured men and women, keeping all the citizens in such danger and terror that when they went outside the town, they went armed and guarded as if they had to advance toward deadly battles.” This is the picture of the antagonist who will come face-to-face with St. Francis – at least as told by the citizenry of the town who, consequently, lived in fear behind their barricaded walls. The town, the people, and the wolf were in need of holiness, healing, hospitality, and hope. St. Francis, upon hearing about the incidents, responded in great compassion for the town, its citizenry, and the wolf – for all God’s creatures. He understood that every side has a story, every side has erred and been harmed, and both sides want the hope and possibility of peace. Francis went into the forest and called out to the wolf to come and meet in peace. Francis’ call was a call to holiness and began the process of healing in the moment of listening to the other, of inquiring why there was such aggressive and brazen behavior.

The wolf was starving and when it sought food among the flocks, the wolf encountered shepherds seeking to protect the flock. From there, tension and aggression escalated on both sides, with fear and hunger dictating the next steps. Francis calls the wolf to remorse and healing for his part in the growing conflict, but also offers a path to hope. Francis proposed a plan in which the wolf would no longer terrorize the town, and the town would open its door in hospitality by taking care of the wolf. The Saint asked the wolf for a sign of acceptance and, “putting out his hand he received the pledge of the wolf; for the latter lifted up his paw and placed it familiarly in the hand of St Francis.” Holiness, healing, hospitality, and hope – the two sides were reconciled. “Finally, Brother Wolf grew old and died. The citizens grieved greatly at his absence.” Some historians have concluded the story is simply fanciful. Others conclude it is a telling of peacemaking that obscures the names of the conflicted parties in order to let the narrative’s power not be interrupted. According to tradition, Gubbio gave the wolf an honorable burial and later built the Church of Saint Francis of the Peace on the site. During renovations in 1872, the skeleton of a large wolf, apparently several centuries old, was found under a slab near the church wall and then reburied inside.

The Story Retold for Our Time

The artist was asked to consider a new presentation of the story of the Wolf of Gubbio through the lens of holiness, healing, hospitality, and hope. We wanted a symbol of this community and one which was not a monument that would tower over us, but a work of art that was inviting and welcoming to all. Fiorenzo Bacci, using his great insight of St. Francis and his life, came back with a draft of his idea. Bacci, who “drafts” – not with pencil and pad, but with bronze – created a work that captured the key moment of the story of the Saint, “putting out his hand he received the pledge of the wolf; for the latter lifted up his paw and placed it familiarly in the hand of St. Francis.”

Francis is shown, not towering over the wolf, but humbly positioning himself as “brother,” as one willing to listen, and to find peace – even if that means possibly making himself vulnerable. Francis comes as one who loves truly and completely, inviting the wolf to that same moment. The wolf is cast as she-wolf, a mother with cubs, whose driving compulsion is the care of her children. The moment chosen from the story depicts the animal welcoming St. Francis’ empathy, showing the typical submissive behavior of its species: tail between the legs, raised ears and open mouth. As a sign of trust and allegiance, the statue captures the moment when reconciliation and peace became possible, when the wolf places her paw in St. Francis’ hand.

The holiness of St. Francis, hospitality in the welcome, healing in the encounter, and the embrace of hope, are moments captured in Bacci’s work. All are moments that are joyful and to be celebrated. That joy is captured with an addition to the story: the cubs playing with Francis’ cords. The entire scene, and all that follows in the story is blessed, as seen in the raised right hand of the Saint. It is our hope that this work of art reminds us and calls us to be a community of holiness, hospitality, healing, and hope – and a community that joyfully celebrates the blessings of God.

The Artist

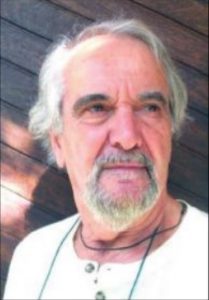

Fiorenzo Bacci was born in 1940 in Perugia, Italy, where he learned the art of sculpting from the local craftsmen. However, his first career was with the Italian Army. He served and retired at the rank of Colonel. In his retirement, he dedicated himself to his first love: sculpting. Bacci’s career has encompassed religious and secular works, not only sculpture, but also altars, altar pieces, and cathedral doors, covering an amazing array of commissions. Within Italy his works are well-known and on display in Cathedrals, churches, palaces, public squares, municipal parks, and a variety of public areas. Bacci also has works permanently displayed in Australia, Egypt, Austria, Germany, and the United States. Currently the sculptor is engaged in two major projects. The first, “Walking the Canticle of Brother Sun,” by St. Francis of Assisi consists in the creation of 10 sculptures for the Saint Francis Literary Park. Founded by the writer Stanislao Nievo, it is a virtual “park” honoring the poem known in English as “Canticle of the Sun” or “Canticle of Creation.” It is the first-known poem written in Italian and is studied by all school children as part of their linguistic patrimony. The second project, titled “Totus Tuus. Towards the House of the Father,” memorializes St. Pope John Paul II through a life-size sculpture which has toured the cities that the pope visited when he was alive. A copy of this sculpture has been permanently placed outside of St. Mary’s Cathedral in Sydney, Australia. To learn more about Bacci and his amazing sculptures, please visit his website.

Fiorenzo Bacci was born in 1940 in Perugia, Italy, where he learned the art of sculpting from the local craftsmen. However, his first career was with the Italian Army. He served and retired at the rank of Colonel. In his retirement, he dedicated himself to his first love: sculpting. Bacci’s career has encompassed religious and secular works, not only sculpture, but also altars, altar pieces, and cathedral doors, covering an amazing array of commissions. Within Italy his works are well-known and on display in Cathedrals, churches, palaces, public squares, municipal parks, and a variety of public areas. Bacci also has works permanently displayed in Australia, Egypt, Austria, Germany, and the United States. Currently the sculptor is engaged in two major projects. The first, “Walking the Canticle of Brother Sun,” by St. Francis of Assisi consists in the creation of 10 sculptures for the Saint Francis Literary Park. Founded by the writer Stanislao Nievo, it is a virtual “park” honoring the poem known in English as “Canticle of the Sun” or “Canticle of Creation.” It is the first-known poem written in Italian and is studied by all school children as part of their linguistic patrimony. The second project, titled “Totus Tuus. Towards the House of the Father,” memorializes St. Pope John Paul II through a life-size sculpture which has toured the cities that the pope visited when he was alive. A copy of this sculpture has been permanently placed outside of St. Mary’s Cathedral in Sydney, Australia. To learn more about Bacci and his amazing sculptures, please visit his website.