The Book of Genesis

Genesis is the first book of the Pentateuch (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy), the first section of the Jewish and the Christian Scriptures – also called the Torah. Its title in English, “Genesis,” comes from the Greek of Gen 2:4, literally, “the book of the generation (genesis) of the heavens and earth.” Its title in the Jewish Scriptures is the opening Hebrew word, Bereshit, “in the beginning.”

It is good to remember that the accounts of Genesis are not newspaper reports or history texts – although they might indeed report or capture events as such. They are the stories of the people of God that were carried and passed on for generations upon generations as the sacred stories, a treasure. They are the stories of how God revealed God’s self to humanity and the people’s response to that revelation. They are an oral history that reflected thought and questions of meaning that only later in time reached a final written form.

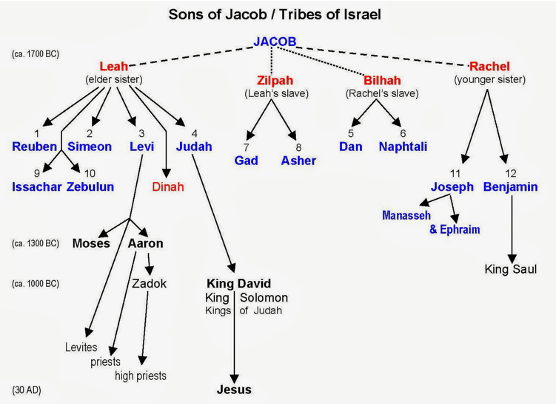

The Book of Genesis is the story of the prehistory of the people Israel. Israel later became a nation only when it came to occupy and rule the land of Canaan. Genesis tells the story of the people Israel beginning with Abraham and Sarah, growing with Isaac and his son Jacob, growing larger still in the 12 sons of Jacob. The people Israel came to identify itself as a federation of 12 tribes in covenant with a God who had brought their ancestors out of Egypt and led them to the Promised Land. The Exodus from Egypt was interpreted as the moment of birth for this nation. But as these tribes consolidated their traditions that spoke of the actions of God in their past, they began to realize that even before the time of the Exodus, God was at work leading them to that moment. The Exodus came to be viewed as the culmination of a process that started when, in the Book of Genesis, God first called Abraham and Sarah and promised to make of them a great nation – as many as the stars in the sky or grains of sand on the seashore. An oral history that reflected thought and questions of meaning that only later in time reached a final written form.

The Book of Genesis has two major sections—the creation and expansion of the human race (2:4–11:9), and the story of Abraham and his descendants (11:10–50:26). The first section deals with God and the nations, and the second deals with God and a particular nation, Israel.

The opening creation account (1:1–2:3) lifts up two themes that play major roles in each section—the divine command to the first couple (standing for the whole race) to produce offspring and to possess land (1:28). In the first section, progeny and land appear in the form of births and genealogies (chaps. 2–9) and allotment of land (chaps. 10–11), and in the second, progeny and land appear in the form of promises of descendants and land to the ancestors.

Genesis 1–11: The creation and expansion of the human race. God makes a good world and installs humans as its rulers. Humanity rebels and ends up ruling the world in a destructive way, leading to violence, death, and the founding of the city of Babylon. God’s response is to set in motion a plan to rescue and bless the whole world through the family of Abraham.

The seven-day creation account in Gen 1:1–2:3 tells of a God whose mere word creates a beautiful universe in which human beings are an integral and important part. Though Gen 2:4–3:24 is often regarded as “the second creation story,” the text suggests that the whole of 2:4–11:9 tells one story.

The plot of Gen 2–11 (creation, the flood, renewed creation) is a pattern that also appears in the creation stories of Mesopotamian literature of the second and early first millennia. A brief comparison of the Jewish telling and the Mesopotamian telling is an interesting way of exploring part of the purpose of oral history: to explain “who we are.”

In the Mesopotamian creation-flood stories, the gods created the human race as slaves whose task it was to manage the universe for them—giving them food, clothing, and honor in temple ceremonies. In an unforeseen development, however, the human race grew so numerous and noisy that the gods could not sleep. Deeply angered, the gods decided to destroy the race by a universal flood. One man and his family, however, secretly warned of the flood by his patron god, built a boat and survived. Soon regretting their impetuous decision, the gods created a revised version of humankind. The new race was created mortal so they would never again grow numerous and bother the gods.

In the Genesis creation-flood story, the one and only God created man and woman in his own image, not as slave but from an outflowing of love. There is a simple verse that speaks volumes about the intended relationship, “…LORD God walking about in the garden at the breezy time of the day.” (Gen 3:8) God provided for the people and was available to them – a much different view of God and humanity. But things still were awry. In Genesis the fall of humanity is attributed the fault to human sin rather than to divine miscalculation (6:5–7) and had God reaffirm without change the original creation (9:1–7). In the biblical version God is just, powerful, and not needy.

These stories reveal a privileged time, when divine decisions were made that determined the future of the human race. The origin of something was thought to explain its present meaning, e.g., how God acts with justice and generosity, why human beings are rebellious, the nature of sexual attraction and marriage, why there are many peoples and languages. Though the stories may initially strike us as primitive and naive, they are in fact told with skill, compression, and subtlety. They provide profound answers to perennial questions about God and human beings.

The first 10 chapters of Genesis include the Creation account, the story of Adam and Eve – as well as their descendants accompanied by the expansion of sin. All leading to Noah and the account of the flood – which is its way is a “restart” for humanity, a new creation, a second chance, a washing clean. From this “restart” the nations arise (Gen 10) from the sons of Noah as well as the Tower of Babel (Gen 11).

“These are the descendants of Shem…” (son of Noah; Gen 11:10) listed until we meet Abram (later called Abraham)

Genesis 11–50: The story of Abraham and his descendants. God makes a promise that He will bless all nations through Abraham’s family. But with aging husbands, impatient matriarchs, blessing-stealing children, and jealous siblings who keep mucking things up, how will God’s promise prevail?

God, having been rebuffed in the attempt to forge a relationship with the nations, decided to concentrate on one nation in the hope that it would eventually bring in all the nations. The migration of Abraham’s family (11:26–31) is part of the general movement of the human race to take possession of their lands (see 10:32–11:9). Abraham, however, must come into possession of his land in a manner different from the nations, for he will not immediately possess it nor will he have descendants in the manner of the nations, for he is old and his wife is childless (12:1–9). Abraham and Sarah have to live with their God in trust and obedience until at last Isaac is born to them and they manage to buy a sliver of the land (the burial cave at Machpelah, chap. 23). Abraham’s humanity and faith offer a wonderful example to all people in trying times.

Placing the events of the life of Abraham and Sarah in history has been much discussed. The consensus of scholars date the account to sometime in the first half of the second millennium. There is unfortunately no direct extra-biblical evidence confirming the estimate. The proper names of people do fit linguistic patterns attested in the second millennium. Evidence to the contrary, it is reasonable to accept the Bible’s own chronology that the patriarchs were the ancestors of Israel and that they lived well before the exodus that is generally dated in the thirteenth century.

Here is the briefest of outlines of the story of Abraham and Sarah:

- Abraham’s call and migration: from Ur of the Chaldes, to Canaan, and to Egypt (Gen 12)

- Abram returns to the promised land from Egypt, separates from his nephew Lot, and receives the promise of descendants: “I will make your descendants like the dust of the earth; if anyone could count the dust of the earth, your descendants too might be counted.”(Gen 13)

- Abraham stumbles upon the war of the four kings vs. five kings. One of the causalities of the conflict was Lot and his people. Abraham and 300 men rescue Lot. At this point Abraham meets and is blessed by Melchizedek, a “priest of the God most high.” (Gen 14)

- God reveals Himself more completely to Abram reaffirming His promises (Gen 15)

- Unbelief of Sarah and Abraham — the birth of Ishmael (Gen 16) from the servant Hagar

- God makes covenant with Abraham (Abram becomes Abraham) and confirms promise to Abraham about a son born of Sarah. (Gen 17)

- The three visitors, God reveals coming destruction of Sodom and Abraham intercedes on behalf of inhabitants (Gen 18)

- Angels warn Lot who leaves Sodom. God destroys Sodom and Gomorrah as Lot’s wife turn into a pillar of salt (Gen 19)

- Abraha, Sarah, and King Abimelech (Gen 20)

- The birth of Isaac, Hagar and Ishmael are cast out into exile. (Gen 21)

- God commands Abraham to offer Isaac, restrains him, and reconfirms covenant with Abraham (Gen 22)

- Death of Sarah and Abraham purchases Machpelah cave for burial place (Gen 23)

There are still 27 more chapters in the Book of Genesis in which we encounter

Isaac (Gen 24-26)

- Isaac and Rebekah, their sons

- Esau and Jacob – and the deception of Rebekah that gives the birthright to Jacob

- Jacob and his wives Leah and Rachel

- The sons of Jacob

Joseph (Gen 27-50)

In the biblical narrative, Jacob’s favoring of Joseph, the son of his beloved wife Rachel, provokes his brothers to kill him. Joseph escapes death through the intercession of Reuben, the eldest, and of Judah, but is sold into slavery in Egypt. Joseph, endowed by God with wisdom, becomes second only to Pharaoh in Egypt. From that powerful position, he encounters his unsuspecting brothers who have come to Egypt because of the famine, and tests them to see if they have repented. Joseph learns that they have given up their hatred because of their love for Israel, their father. Judah, who seems to have inherited the mantle of the failed oldest brother Reuben, expresses the brothers’ new and profound appreciation of their father and Joseph (chap. 44). At the end of Genesis, the entire family of Jacob/Israel is in Egypt, which prepares for the events in the Book of Exodus.